Betrayal is not merely a moral failure: it is an anthropological rupture that questions identity, growth, and the courage to become oneself.

Introduction

Betrayal remains one of the most condemned and, at the same time, most pervasive experiences in human life. It is often reduced to sexual infidelity, ethical weakness, or relational failure. Yet, when examined more deeply, betrayal reveals itself as a structural event of human existence—a critical threshold where identity, bonds, and meaning are reconfigured.

Drawing inspiration from a well-known reflection by Umberto Galimberti, this article offers an anthropological and existential reading of betrayal: not to absolve it, but to understand its symbolic and transformative function.

Betrayal Is Not (Only) Desire

Anthropologically, human beings are born into trust. Someone feeds them, protects them, gives them a name. In this phase, fidelity is not a choice but a vital necessity. Over time, however, what once ensured survival can become an obstacle to growth.

Betrayal emerges when identity begins to chafe—

when it no longer coincides with the role assigned, the image loved by the other, or the belonging that once guaranteed security.

In this sense, betrayal is not primarily erotic but symbolic: it is the often clumsy attempt to escape a received identity in order to seek one that is unprotected, uncertified, and no longer guaranteed by another’s love.

Fidelity and Its Shadow

Every form of fidelity contains an element of possession.

To be loved often means to be recognized on the condition of remaining the same.

Yet human identity is dynamic, excessive, restless.

When fidelity does not even allow for the possibility of betrayal, it ceases to be a choice and becomes emotional dependence.

Seen this way, betrayal is not the opposite of fidelity, but its necessary shadow—the element that gives fidelity depth and truth.

Without the possibility of farewell, fidelity remains childish, naïve, defensive.

Judas: The Necessary Betrayer

Here the figure of Judas Iscariot takes on decisive symbolic power.

Judas is not only the archetypal traitor of Christian tradition; he is also the one without whom Jesus’ destiny could not unfold.

In the Gospel narrative, Jesus chooses Judas, calls him, includes him.

He does not ignore the possibility of betrayal—he assumes it.

Judas’ betrayal is not a narrative accident, but a necessary rupture through which the mission passes into death and, paradoxically, into meaning.

In this light, Judas becomes a liminal figure who reveals an unsettling truth:

sometimes we choose those who will betray us because only through that wound can we encounter our destiny—or at least ourselves.

The Betrayed and the Greatest Risk

Those who are betrayed experience radical disorientation.

Yet the deepest danger is not the loss of the other, but the devaluation of the self.

When identity has been grounded entirely in being loved, betrayal exposes a painful truth:

I was myself only as long as the other confirmed me.

In this sense, betrayal can become—if endured—an emancipatory event even for the betrayed, forcing the reconstruction of the self outside the gaze that once guaranteed it.

Fidelity, Betrayal, and the Birth of the Self

Perhaps life is not written under the sign of pure fidelity, but in the tension between fidelity and betrayal.

Fidelity preserves; betrayal exposes.

The former protects; the latter risks.

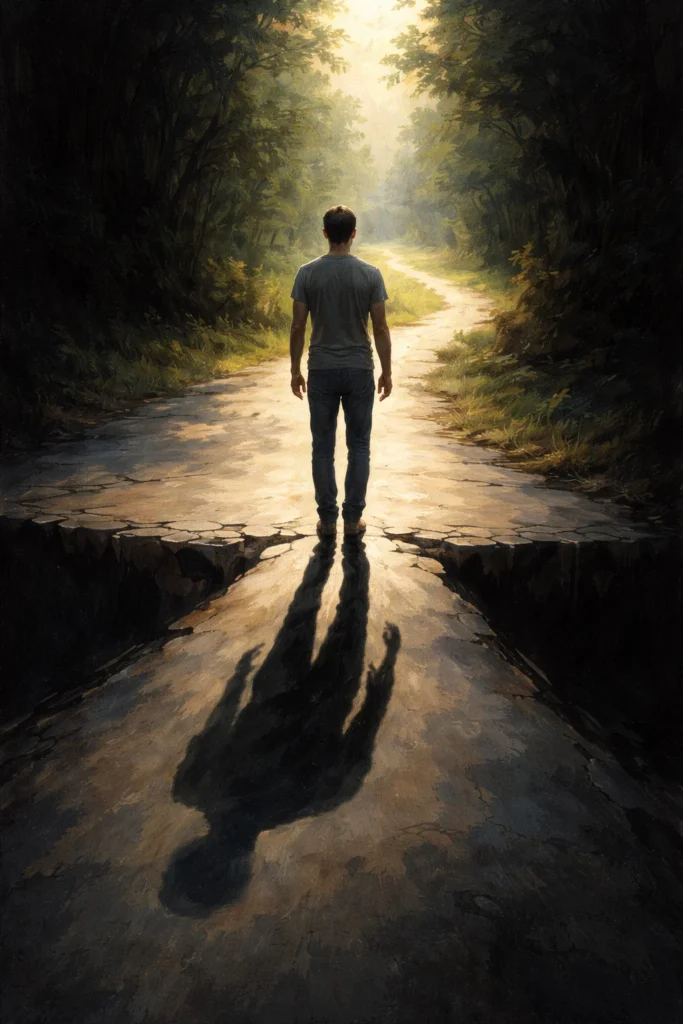

Only those who pass through this tension stop living “on loan” and accept the highest risk of human existence:

to encounter themselves, even at the cost of losing a love, a belonging, or a ready-made identity.

Because we are not born only once.

We are truly born when we have the courage to say goodbye.

Conclusion

To understand why we betray is not to justify the pain betrayal causes.

It is, however, to restore betrayal to its anthropological complexity, freeing it from moral simplification and recognizing it as one of the most dramatic—and revealing—sites of the human condition.